Or, the importance of accurate attribution

You’ve probably read a book that has a quote at the start, or maybe each chapter opens with a quote. They’re called epigraphs, and their purpose is to give the reader an idea of the tone or theme the story intends to set.

I love a good quote, but they can go awry. You see the quote online, you like it, you copy and paste it into your manuscript, done. But did that person actually say those words? And were those words the actual words they used?

Here’s a famous Oscar Wilde quote: “Be yourself. Everyone else is already taken.” But did he say that? Turns out, there’s no evidence for him saying it. Not in any of his writing, not in any of his speeches, not during any of his soirees.

Why accurate quoting matters

With misinformation more common than ever and the tendency of generative AI to make up quotes, it’s essential your quotes are accurate.

Let me emphasise that as much as I can with bold, underline, italics, and all caps: it is ESSENTIAL your quotes are accurate.

Correctly attributed quotes show your reader that you care and that what you say is credible. You build trust with your readers when you get details like this correct.

It’s also plain polite. You’d be annoyed if someone misquoted you, especially if your name got attached to words you never said and those words ended up in print.

Verifying quotes

So, how do you verify quotes? Wherever possible, go back to the original source. Be the Indiana Jones of sourcing quotes.

If the quote came from a book: If you’ve got the book on your shelf or you can get it from the library, pull it out and note the title, author, year it was published, and page number.

Or, in Google, put the quote in quote marks and hit search. The quote marks mean Google searches for those exact words, in order. You should get results that point you in the right direction. Google Books will often give you page snippets.

If the quote came from a speech: verifying quotes from speeches is a little more tricky. Use the Google quote mark trick as a starting point, then try to find a reputable source. Graduation speeches are often published on university websites. YouTube may have a video of the speech. If it was famous enough, it may have been included in book compilations of famous speeches.

If the quote is a song lyric: artists’ websites may list lyrics, and Spotify often shows lyrics. You can check sites like Shazam and AZLyrics to compare lyrics. But please, don’t use lyrics unless you have permission.

Other great resources are Quote Investigator and Snopes.

Big caveat: if you’re using Google (or any search engine, really), don’t rely on the AI Overview. Follow the links, dig deeper, and try to get to the original source.

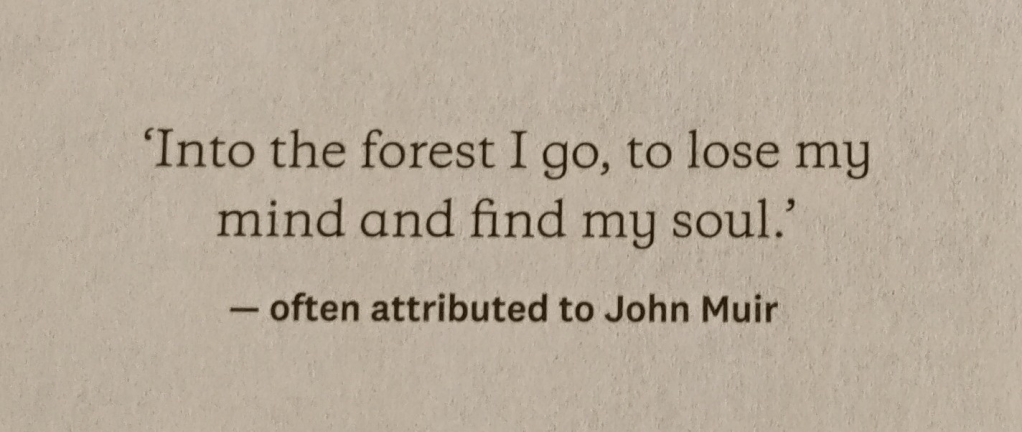

If you really can’t find the source, then you can get away with saying “commonly attributed to So-and-so”, but use that only as a last resort.

Here’s an example of using “commonly attributed to” from Victoria Bruce’s Adventures with Emilie:

Citing your quotes

Okay, you’ve verified your quotes. You have the page number from the book or the timestamp from the video. Do you need to include the full reference like you’re writing an essay for high school?

You don’t necessarily need to go that far.

If you’re working with a publisher, they may ask for sources to cover off their due diligence requirements. They may even include sources in the copyright notice page, especially if you needed permission to use the quote.

If your book includes endnotes, then you can include the source there. Sophy Roberts includes full sources for the epigraphs in A Training School for Elephants in the notes. She’s a master of citing her sources and going the extra mile to make sure her quotes are accurate.

Even if you don’t end up including the full source in your manuscript, you can be content knowing that you’ve done your best, you’ve done your readers a service, and you’ve honoured the person who said those words in the first place.

What’s next?

Go ahead and include epigraphs in your story. Just make sure you verify those quotes the best you can.

As Ernest Hemingway never said, “Write drunk, edit sober.” (We can probably thank someone completely different for this gem: Peter De Vries.)

Discover more from Deborah Shaw Adventure Editing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.